Human-centred design in hospital technology

If you have ever read The Design of Everyday Things by Donald Norman, you have probably heard of the term, “human-centred design”. In simple terms, human-centred design is about designing things for human users. This may sound like an obvious and simple task, but it really isn’t, and is often taken for granted.

In Made to Stick by Chip and Dan Heath, they introduce the idea of “The Curse of Knowledge”. You are cursed with knowledge when you are no longer able to put yourself in the shoes of someone who does not know what you know. When you try to explain something to someone, you make all sorts of assumptions about what the other person knows. As a result, the other person has a difficult time trying to understand what you are trying to explain to them, for no fault of their own.

Human-centred design is all about designing things with the mindset that the people using what you are designing may not know everything that you may assume that they know. This can include things as menial and innocuous as doors (are you supposed to push or pull the door to open?), or it can include life or death situations, such as nuclear power plant controls (what does this big yellow button do?).

It’s unfortunate that designers are often taken for granted, especially in the field of technology. Many people seem to think that design is only about making things look pretty. This can have disastrous consequences, especially in the healthcare IT industry — for example, if a poorly-designed user interface resulted in incorrect information being inputed by a healthcare worker into an electronic system.

As someone who wanted to break into the healthcare IT industry myself around three years ago, I wanted to set myself apart from other programmers, who may look down on design as a lower tier craft. I wanted to emphasize human-centred design, as opposed to only focusing on technical ability. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to demonstrate this as part of the interview process for a healthcare software company that I really wanted to work for.

The Opportunity

A few years ago, I was given the opportunity to meet with the CEO of a healthcare software company that I was interested in working for. Originally, the meeting was supposed to be for coffee, and I wanted to pick the CEO’s brain on what the company did. This somehow ended up becoming my first interview with the company after he introduced me with a manager that was hiring.

I got a call back after my first interview, and was asked to prepare a demonstration for my second interview in two weeks. They kept the requirements very open-ended: as long as it utilized their software (a healthcare system integration engine) in some way, and as long as it highlighted my own skills that I believe I would be bringing to the company, then it followed their requirements.

Getting to Work

Before I even thought about the kinds of technologies that I would be using to perform my demo, I first took a few steps back. I wanted to cater my demo to try and solve some kind of problem in healthcare IT, and I wanted to focus on the process of coming up with solutions.

In other words, I wanted to build something that solved a real problem, rather than building something that was focused on the technology used. Whatever technology would be used should serve the solution to the problem being solved, and not the other way around.

After watching a YouTube video showing Travis Neilson using design thinking to solve a problem, I took down some notes on what the process would look like:

-

Discover: Define and understand the problem using empathy to identify needs and narrow down the focus.

-

Brainstorm: Use the knowledge gained from the discovery process to come up with ideas to solve problems (10x your ideas).

-

Prototype: Communicate ideas and solutions to problems using insights learned in the previous steps.

-

Repeat.

Discover

Being a fresh university graduate at the time, I admittedly had no experience in the healthcare IT industry. In fact, my degree was not even related to software development — I majored in astrophysics.

To start off, I began doing some research on healthcare IT. What kinds of technologies were used, and how does it all fit in the context of healthcare? I read up on EMRs and EHRs, how patient data was being managed, and how healthcare providers were using healthcare technology.

After an entire week of doing research (while also learning how to use the software that I had to use in my demo), I came up dry on ideas for what I should build.

I then quickly realized that I was focusing too much on the technology part — exactly what I was trying to avoid to begin with. I needed to focus less on what technologies were being used, and more on problems that needed to be solved.

For now, I needed to ignore healthcare IT, and instead learn more about what healthcare professionals do on a regular basis. I needed to learn more about the problems that they faced. I needed to do user research.

Doing User Research

Around that time, I had just happened to have become sick. I paid a visit to my family doctor, and took this opportunity to ask him questions about how he used technology on a regular basis. I also asked him about what kinds of problems he was facing with his workflow.

Afterwards, I also remembered that I had a few friends who had studied nursing, and were just entering the workforce. I reached out to a few of them, and asked them questions about problems and difficulties that they were facing in their work.

In hindsight, they were great subjects for user research, as they were just starting their jobs, and had not yet experienced “the curse or knowledge”. They may have had insights that those with more experience may overlook, for example.

From those discussions, I made the following notes:

-

Healthcare workers typically do not know the low-level technical details of the technologies that they use — they treat technology as a tool that they use, and nothing more.

-

Family physicians are slowly making the switch to EHRs — many are still storing patient information in filing cabinets and sending patient information through fax.

-

A big problem that nurses face in the ER is how to efficiently improve the decision-making process. For example, there is a need for better organization and ease of managing incoming information (i.e. triaging incoming patients).

-

Drawing on my experience volunteering at a hospital, I also recalled that many of the user interfaces on computers that healthcare providers had to interact with were difficult to read.

The big insight that I gathered from all of this was that there was an opportunity to solve an important problem in emergency rooms, especially as hospitals are moving towards integrating modern technology into their workflows.

Healthcare providers need to be able to make quick and informed decisions under stress. Knowing patient history is crucial when treating incoming ER patients. They also need to quickly make important decisions based on need and priority.

The problem that I would be attempting to solve, therefore, was to somehow improve the decision-making process in ER departments.

Brainstorm

Now that I had real insights on actual problems that healthcare providers were facing, it was time to brainstorm on how to try and solve some of these problems.

There are many techniques for brainstorming, but one technique that I used based on watching Travis Neilson was to try and “10x” my ideas. This technique involves starting with any idea, and trying to come up with 10 more ideas. No matter how crazy the ideas were, always try and “yes, and..” the ideas, one after the other.

The main points that I tried to focus on with my brainstorming were ways to allow healthcare workers to quickly get important medical information for patients that come into the ER, how to improve the way that patient information is displayed to healthcare workers that would make it easier for them to read (especially when they are under stress), and to somehow make it more efficient for healthcare workers to triage incoming patients so that they could focus on serious cases first.

Prototype

The goal of prototyping is not necessarily to come up with a perfect product that solves everyone’s problems right away, but to attempt to communicate ideas and solutions to problems using insights learned, keeping in mind that this is all an iterative process. This involves defining user stories, sketching some wire frames or diagrams, quickly building a prototype, and then testing this prototype.

From all of the brainstorming that I did, I ended up on settling with the idea of building a small application that would allow healthcare workers to achieve the following user stories:

-

Able to quickly search for a patient’s information in a database, and display that information in a user-friendly interface.

-

Allow for additional information to be inputted by the healthcare worker, and then for a rating to be given to the patient based on how serious their condition is when they enter an ER.

-

There will be a dashboard that lists all of the patients that have come into the ER, clearly displaying their information and how serious their state was (using the rating system), to allow healthcare workers to focus on the important cases first.

Although a very basic solution, this was a perfect starting point for building a demo for my interview. I would utilize the healthcare system integration engine that I been learning how to use to query a database, and return the information that I needed. I could then use some basic web development skills that I had to build a simple dashboard for displaying and inputting more information.

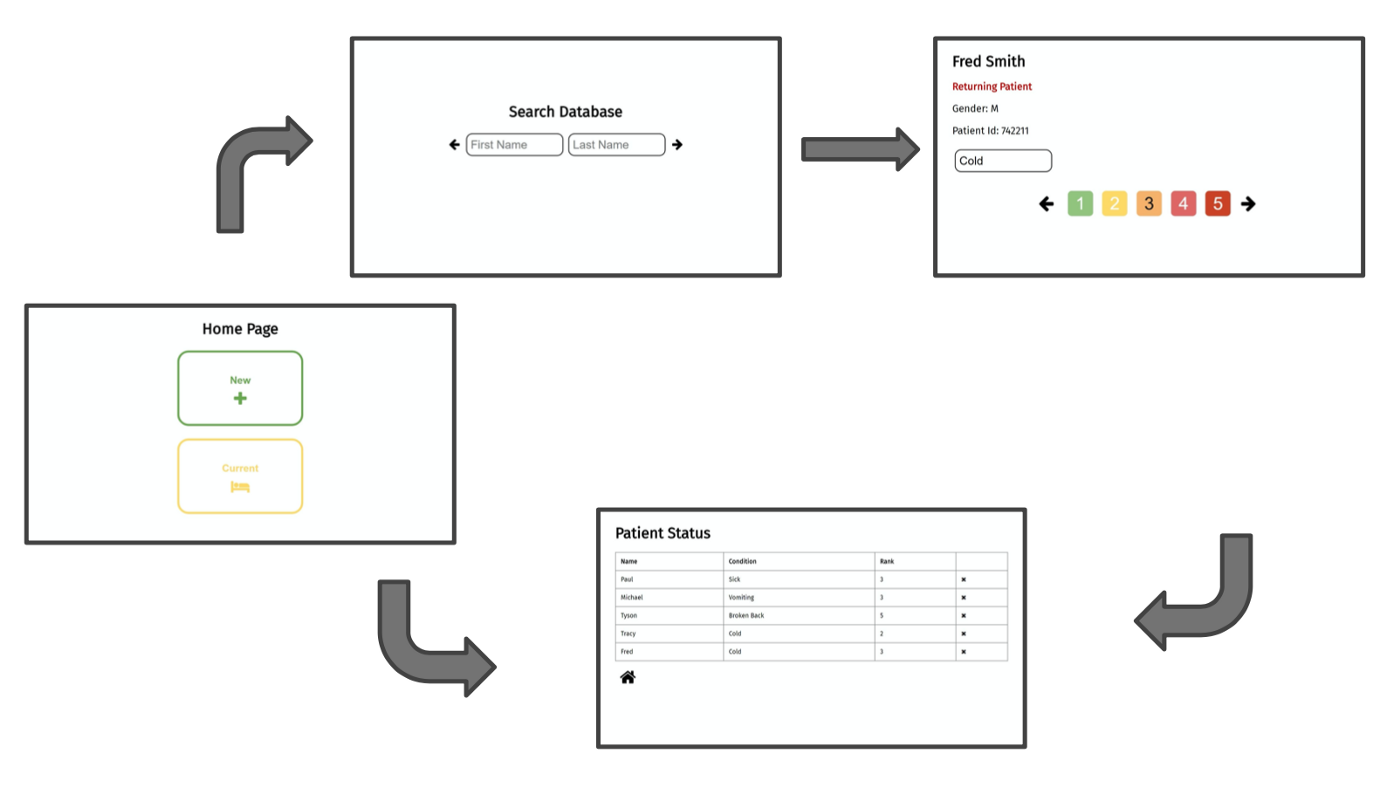

After sketching out a few ideas on how this would all look, I came up with the following wireframes showing the general workflow of the application:

-

When a healthcare provider opens the application, they will see a home page with two large buttons, indicating if they want to add a new patient, or view current patients in the ER.

-

If they choose to view current patients, then they are taken straight to the patient status screen.

-

If they choose to add a new patient, then they will be taken to a screen that will allow them to search the database for any information on the patient.

-

Once they find the patient, they can enter in information about the state of the patient, and assign a rating from 1–5 on how serious the patient’s condition is.

-

Upon entering this information, they are taken to the patient status screen with all of the current patients in the ER, with their information and condition clearly presented in the form of the 1–5 rating that they had entered in step 4.

I attempted to make this interface as easy to read as possible, with large fonts, large buttons, plenty of whitespace, and I also tried to make the interface look visually attractive.

Once I had everything planned out, I went ahead and started writing some code (finally!). Without getting into too much detail, I utilized Bootstrap and AngularJS for the frontend. The backend was handled by the integration engine, which I used to serve the web pages and query a SQLite database that I was using to store patient information.

The Interview

I ended up almost pulling an all-night the night before my interview to get the prototype up and running. Fortunately, coming up with the idea and knowing what to build was where the majority of the work was. This was where I wanted the focus of my interview to be.

The code that I had put together was not perfect, or anything I would even consider good. It was very messy, had no error handling for invalid inputs, did not consider cases such as when identical names exist in the patient database, and there were no security measures implemented at all. But it worked as a prototype.

The interview ended up going very well. I went in with the mindset that I was most likely not going to get the job, as I was probably not qualified for the job (I was an astrophysics major, after all). I wanted to use this as an opportunity to add something to my portfolio, as well as potentially network further with the hiring manager. If anything, I learned a lot throughout this whole process, and that was already a big win for me.

Of course, the solution that I had come up with was a very naive one — I had no delusions or any ideas that this would actually help in a real ER setting, and it’s possible that there was already a better solution out there for the problem I was trying to solve.

The point of going through all of this was not necessarily the final product, but rather the thought process that I went through to come up with a solution.

Part of what makes human-centred design so powerful is that it is an iterative process. If I were to truly practice human-centred design, I would do more user research, test this prototype in the field, gather feedback and lessons-learned, and then repeat the whole process again, using the insights that I gathered the first time. Given that this was for a demo for a job interview, I only did this process once.

In the end, miraculously, I ended up getting a job offer the very next day. The hiring manager (who is still my current manager) was impressed.

Having gotten the job, I looked forward to truly learning more about the healthcare IT industry, and hopefully using the problem-solving skills that I learned throughout all of this to solve real problems in healthcare IT.